Dishing with DKG: Musician Corb Lund on the death of Ian Tyson, coal mining in the Rockies and woke self-censorship

'I’m not political. I really don’t enjoy this,' Lund says. Yet here he is. Point-man on a political issue, so egregious and in his backyard, that he’s in hip-deep

Singer Corb Lund: “It’s healthy for people in society to have art that doesn’t have to be political. It’s good for the soul.”

PHOTO BY MIKE DREW/POSTMEDIA/FILE

Ian Tyson was his friend and mentor.

“Ian literally has a song with the lyrics, ‘When I die, let me go naturally’ and ‘don’t let them put no tubes in me,’ Corb Lund grins, “and he got his wish.”

It’s the day after the passing of 89-year-old country music icon Ian Tyson and I’m at a bar in Calgary’s trendy Inglewood community sitting across the table from Corb for an interview, set up weeks ago, to talk about why he’s so exercised about protecting the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains from open-pit coal mining. I expect to find him wistful but this cowboy crooner from southern Alberta, a power-through kind of guy, is regaling me with stories of Tyson.

“Ian recently sang on an AC/DC cover with me. We sang Ride On, which was pretty hip of him. He was doing pretty cool s—, right to the end,” Corb shares, again flashing that big smile.

He’s reflective for a moment: “It’s funny with Ian… we spent a lot of time together and it didn’t feel different than hanging with other musician friends my own age. And every once in a while I’d look over and see the Martin guitar he wrote Four Strong Winds on or a picture of Neil Young and it would remind me… I was aware of his legend and his stature, but he’s also a friend.”

The wait staff in the Off Cut Bar of the Nash restaurant, an upscale watering hole, recognize Corb as soon as he pulls off his wool toque and stand by, eager to serve. I’m already imbibing a local microbrew, Jasper Brewing Co.’s Crisp Pils; Corb orders a coffee, black, and water. “Sparkling or still?” the waiter asks. “Tap water’s good,” Corb replies in a flat voice. In a quick look at the beer menu, he passes over the microbrews and their “fruity flavours” and orders a Kokanee.

When all three drinks land on the small table between us, it’s obvious to all the guy is parched.

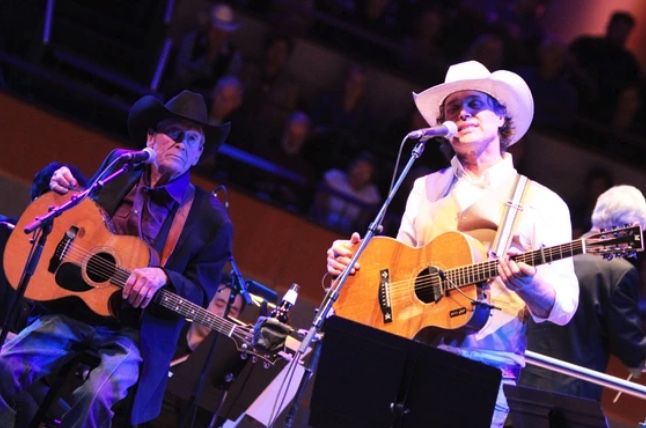

Ian Tyson left, and Corb Lund perform in 2019.

PHOTO BY FISH GRIWKOWSKY/POSTMEDIA/FILE

Refreshed, he launches into another Tyson story. “Bob Dylan’s ex wrote an autobiography years ago and claims that Ian was the one who introduced Bob Dylan to marijuana and Ian told me he thought it was plausible; he didn’t remember it specifically, but thought it was probably true. And then Ian went on to say that it’s widely known Bob Dylan introduced the Beatles to marijuana so if that’s true it makes me the f’ing king.”

We both burst out laughing. It’s beginning to feel like a wake.

The waiter reaches in to press down the plunger on the fancy French coffee press in front of Corb. “May I pour this out for you?” he offers. “No buddy, I can do it,” Corb replies.

Whiling away the afternoon, reminiscing about Tyson, is tempting. As a segue into Corb’s anti-coal-mining crusade, I ask him if he asked for Tyson’s guidance on his advocacy role. For the past 18 months, Corb has been the loudspeaker for a diverse group of people — ranchers, hunters, fishermen, Indigenous peoples, environmentalists, municipalities — who have come together to push back against the government of Alberta’s decision to rescind a Lougheed-era moratorium on coal mining along the eastern slopes of the Rockies.

Tyson didn’t have a lot of advice for Corb. Perhaps, Corb muses, because his own experience trying to stop construction of the Oldman Dam in southern Alberta, decades ago, didn’t turn out all that well.

Albertans are weary of the rich and famous showing up in Fort McMurray, telling us to shut down the oil sands. Aren’t you at risk of the same criticism, I ask? “Yes, I get my share of ‘shut up and sing’. But there are reasons it doesn’t apply to me: One, I educated myself on the issue. Two, I personally drink the water out of the Oldman River in Lethbridge, it’s literally in my backyard.”

Fair enough.

Do you get called out for NIMBYism? He’s thought about this. Is it any worse to keep mining metallurgical coal here, or in Ecuador, Nigeria or Brazil where large-scale mines aren’t likely to be shut down?

Then I point blank ask him: Are you anti-development?

That sparks a feisty rebuttal: “I’m not anti-resource. This is just a bad idea with very little upside. Tiny trickles of royalties and a handful of jobs that have to be weighed against other jobs lost.” And there’s the risk to the water and the cost of reclamation. And how do you reverse the policy once powerful mining companies have a toehold?

When I point out that Charlie Angus (a former musician and now NDP member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay, Ont.) got drawn into politics when he took a stand against Toronto garbage being dumped into a former mine site in his backyard in Northern Ontario, Corb openly bristles: “I’m not political. I really don’t enjoy this.”

Yet here he is. Point-man on a political issue, so egregious and in his backyard, that he’s jumped in hip-deep: “I’m a megaphone for the 75-80 percent of Albertans who don’t want coal mining in the Rocky Mountains and I won’t let go until they fix it.”

For a 53-year-old guy who loves music, above all else, none of this is comfortable. In fact, there are many changes afoot, including cancel culture, that make him uncomfortable: “I spent my life being a rebellious, swash-buckling, write-whatever-I-want guy, and the last couple of years, there’s been a cloud of anxiety over me when I write… I feel fear, it’s not debilitating, but I’m not as free as I used to be.”

Corb has been touring non-stop and welcomes an upcoming break to write songs. He may, or may not, write about coal mining; he doesn’t want to tether his music to this cause.

“Willie Nelson is one of my heroes, and he always brought people together in a bar — hippies, bikers, cowboys — and I think that’s good for people. It’s healthy for people in society to have art that doesn’t have to be political. It’s good for the soul.”

Now that sounds like the lyrics to a song that Tyson would enjoy.

Link to original article: National Post