Dishing with DKG: Edmonton AI guru Rich Sutton has lost his DeepMind but not his ambition

Dishing with DKG: This is a new conversation series by Donna Kennedy-Glans, a writer and former Alberta cabinet minister, featuring newsmakers and intriguing personalities.

This week: AI rock star Rich Sutton.

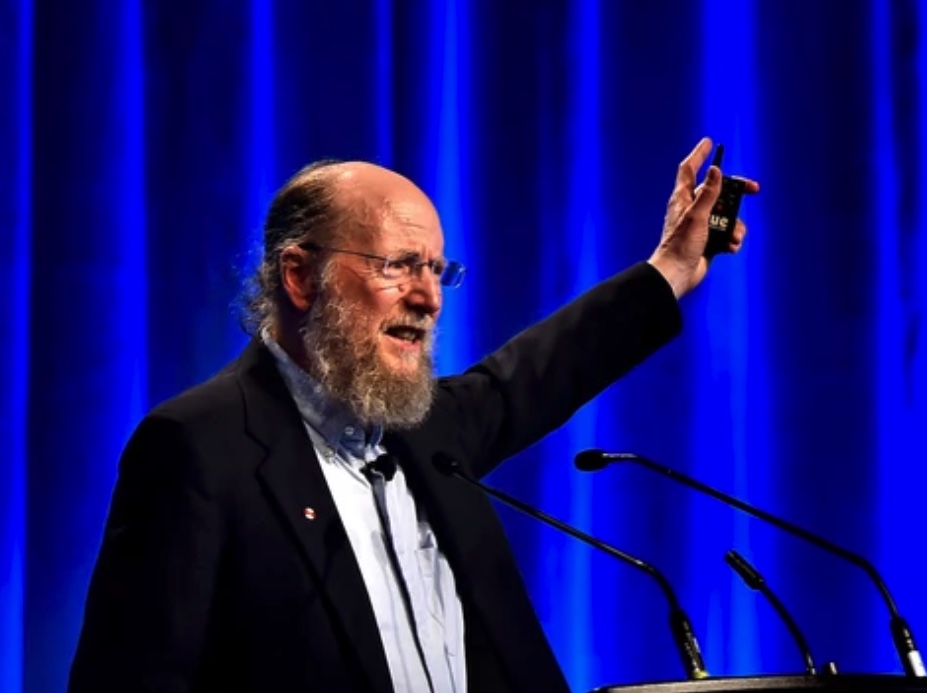

Professor Richard Sutton has expressed frustration with Big Tech’s emphasis on commercial applications of AI research. “That is unfortunate, I think. That’s going to be seen as a mistake in the long run,” he said.

Photo by Ed Kaiser/Postmedia/File

What should one make of Rich Sutton? He’s a rock star in AI (artificial intelligence), and a geek to meet.

In 2017, he partnered with Google’s DeepMind project, opening its “first ever international AI research office” in Edmonton, in collaboration with the University of Alberta.

AI machine learning occupies a lot of bandwidth in the news cycle. With all the hype, it’s easy to overlook Google’s late January decision to shutter Edmonton’s DeepMind lab. In the midst of a heightened AI race, why would Google put the brakes on pioneering research at an Alberta lab?

It’s been a tough couple of months for Rich Sutton. He also lost his father. But when we connect for conversation, I find him remarkably sanguine in his black-and-white plaid flannel shirt, trim grey beard, earbuds and hair that’s long enough to be worn in a ponytail.

Rich looks every bit the quintessential researcher. A guy who has devoted his life to figuring out ways to teach a machine to learn, through trial and error. That’s his specialty — reinforcement learning.

A Canadian citizen since 2015, with his expertise, the erstwhile American is a hot commodity and could work anywhere.

“Are you staying in Alberta?” I ask.

“That’s the plan at present,” he answers, then confidently declares, “I’m going to find a way for it to continue to be really good without DeepMind.”

And what does this pioneer of reinforcement learning have in mind?

“I’m going to make a non-profit research organization, for pure research, and we’ll be funded by donors and corporations that are interested in seeing the research done rather than making money out of it. And because of that, it will be entirely open and there will be no need to hide, or to patent things.”

This sounds familiar. OpenAI, co-founded by Elon Musk as a non-profit in 2015, pledged to advance technology for the benefit of humanity. In 2019, the company changed course to allow big investors, including Microsoft, to chase corporate profit.

“This sounds like a Canadian edition of OpenAI,” I suggest. Rich agrees: “That is actually a pretty good way to think about it. Open AI as it used to be. Open AI when it was non-profit, before it became commercial.”

Rich hasn’t pitched the idea to Elon Musk, yet. He knows he needs to find like-minded champions of Big Science; people interested in doing the research needed to create the future.

His tone is even, but he doesn’t quite hide his frustration with Big Tech’s emphasis on commercial applications of AI research. “Whatever the reasons for the decision (to exit the research lab in Edmonton), the effect of the decision will be to shift the emphasis within DeepMind less toward reinforcement learning and more toward things like large language models,” Rich explains. He adds: “And that is unfortunate, I think. That’s going to be seen as a mistake in the long run.”

Then he qualifies his point: “But who am I? … I don’t have the conceit of claiming that I know what business decisions should be made or what political decisions should be made. Those are for other people. I just know what I should do. I want to work on the prize: Understanding intelligence.”

In 2003, Rich was invited to come to the University of Alberta. It was a time of “AI Winter” in the United States (funding for researchers with ideas like Rich’s had dribbled to a trickle). Rich was in remission from cancer at the time, and politics cinched his decision to move. George Bush was “invading other countries without reason,” he said.

I want to believe that Rich can gather a team to stay in Edmonton and build out his vision.

“They say that Edmonton is sticky,” Rich observes, “That somehow people end up wanting to stay, and we don’t understand it because it is cold. But it’s a good place to grow up. It has a good feeling to it. People pull together.”

Given the fear, distrust, and public uncertainty about the implications of artificial intelligence technology — I’m reminded of the emotions provoked by stem cell research— I also wonder if Rich has the chutzpah to pull off an Alberta-based OpenAI. He is uniquely suited for the task. He checks off all the academic boxes. He’s a known known in the world of AI. He’s also libertarian and thinks, deeply, about why and how it’s OK for people to want different things and be unconstrained in their individual choices. And he applies this thinking to AI.

“When we make AI, what will their goals be? Will we allow them to have independent goals or will we require their goals to be the goals that we have? This is called the alignment problem. Can AIs be free or should they be tightly controlled? Should people be allowed to be free or should people be tightly controlled? It’s the same thing.”

Investing in Rich Sutton’s vision for Edmonton as an AI centre of excellence ought to be a no-brainer: imagine scores of grad-student geeks with their whiteboards and fanciful math.

Google and its parent company Alphabet are now digital juggernauts, but less than three decades ago, the search algorithm that revolutionized the internet was mere gobbledegook on a whiteboard. From such beginnings, rock stars are born.

Link to original article: National Post